KENSUP in Action: Inside the Ministry—On Site in Kibera

“My grandmother never went to school, but she was a wise woman,” Charles Sikuku said as he poured some hot water into his teacup. “She would ask me all the time: Why do people do what they do? Why do they go to work? Why do they do this? Why do they do that? But at the end of the day, she knew exactly why.” He looked up from his cup. “It’s all because of the stomach!” The director of Slum Upgrading at the Ministry of Housing laughed out loudly and took a sip of his tea. We all joined in–laughing, sipping.

Not only because of this anecdote did the 17th of January turn out to be one of the most memorable days of the Nairobi studio trip. It was also because after having visited the permanent decanting site for temporary relocation on the edge of Kibera two years ago and having read and heard advantages and shortcomings of the Kenya Slum Upgrading Programme (KENSUP) in quite some length, I finally saw the end product: the permanent relocation site for over 1,000 households in Soweto East A.

In our morning meeting at the Ministry of Housing, Mr. Sikuku provided a comprehensive overview of KENSUP and its relationship to the Kenya Informal Settlements Improvement Project (KISIP). While KISIP was a project with a limited life time, KENSUP would continue to exist “for quite some time,” he said. In line with the Millennium Development Goals, specifically Number 7 target 11 (improving the lives of 100 million slum dwellers by 2020) and conceived by two partners—UN-HABITAT and the Kenyan government—KENSUP is the result of a 2000 meeting between the then President of Kenya and the Executive Director of UN-HABITAT. Allegedly, the Executive Director offered to spearhead a Kenyan slum upgrading program—starting with its largest slum: Kibera. The grant agreements was signed in July 2002 and a Memorandum of Understanding, put into place on the 15th of February 2003, laid down responsibilities to upgrade informal settlements in Nairobi, Mavoko, Mombasa and Kisumu.

According to Mr. Sikuku, the government of Kenya “must lead as an example” on the topic of slum upgrading. It is for this reason that the president himself acts as the patron of this particular program. The realization that slum upgrading was an essential government responsibility had been reached over time, as reflected in the increasing amounts of funding the government allocated towards slum upgrading over time. From a mere 1 million shillings following Independence, to 5 million in the 1990s, then 20 million, then 300 million. “Now, it is billions,” Sikuku announced proudly.

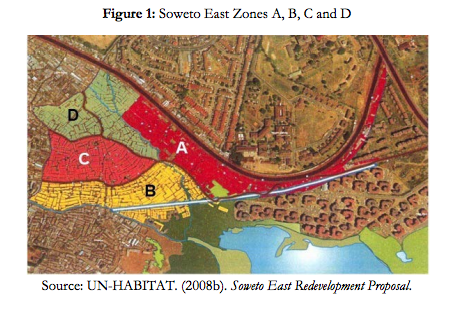

The decanting site, in fact, can be seen as KENSUP’s go-to example. Soweto East Zone A was the largest zone within the Kibera village Soweto East. The area accounts for 37% of the houses in Soweto East, home to 19,000 residents.

Initially, Soweto East Zone A residents were supposed to temporarily relocate to flats in Athi River. The problem was that Athi River was 23 kilometers away from Kibera—a tragedy to local social and economic networks. After an intervention by Prime Minister Raila Odinga, the temporary relocation site was shifted to Lang’ata, southwest of Kibera. The first phase in the Soweto Kibera pilot began in September 2009 with 5,000 relocated residents. Today, the 632 three-room units—each at 50 square meters including a kitchen, a toilet, a shower and a small veranda for laundry washing and drying—in 17 five-story buildings hold around 1,800 households, about one household per room. Depending on your source, a room goes for 500 to 1,000 Shillings a month, a high price that some Soweto East tenants refused to pay. For construction of the permanent relocation site, they were moved to Zones B, C or D of Soweto East.

Initially, Soweto East Zone A residents were supposed to temporarily relocate to flats in Athi River. The problem was that Athi River was 23 kilometers away from Kibera—a tragedy to local social and economic networks. After an intervention by Prime Minister Raila Odinga, the temporary relocation site was shifted to Lang’ata, southwest of Kibera. The first phase in the Soweto Kibera pilot began in September 2009 with 5,000 relocated residents. Today, the 632 three-room units—each at 50 square meters including a kitchen, a toilet, a shower and a small veranda for laundry washing and drying—in 17 five-story buildings hold around 1,800 households, about one household per room. Depending on your source, a room goes for 500 to 1,000 Shillings a month, a high price that some Soweto East tenants refused to pay. For construction of the permanent relocation site, they were moved to Zones B, C or D of Soweto East.

As we entered the complex, I immediately noticed a difference to the last time I had visited: no informal shops. While ground-floor balconies were previously used to continue running small informal markets, they no longer exist. One of our Kenyan partners had told me about the ban of informal trade within the site. She had called it problematic.

Of course, the decanting site project has not been without its challenges, especially with informality. One of the problems the Ministry of Housing has encountered are illegal sub-rentals. “People in slums are different—just give them something good and they’ll sell it,” one of our guides at the decanting site said. To avoid this trend, residents are now requested to provide documentation to prove whether they are indeed family members who are temporary sub-letting from official decanting site tenants.

Water delivery appeared problematic as well. As we listened to our guide by the administrative buildings, long lines of people equipped with empty water canisters were waiting close-by. When I asked why they were there, he said that the main water pipe leading to the decanting site and the entire neighborhood had had a leakage problem for the past few months. The pressure was simply not strong enough to pump the water directly to the tenants’ apartments.

The decanting site has also been ripe with controversies, reported in the local press, surrounding eviction of families who could no longer afford the rent or others who had illegally been brewing chang’aa inside their houses. Amnesty International as well as UN-HABITAT in 2009 released documents that clearly called into question the process of relocation, the level of affordability and the quality of housing.

Finally, there is, of course, the eternal dilemma of ownership. According to a survey conducted by UN-HABITAT, a significant number of Soweto East A residents would have preferred to continue a rental arrangement instead of owning it. Urban residency is often regarded as transitional rather than permanent.

Yet, the permanent relocation site with a permanent ownership structure is well on its way. Walking around the extremely familiar construction site–blue helmets protect us—it is clear that this is an occasion of limited access. We are even allowed into the room where maps, plans and time schedules spread across the walls.

The buildings are, indeed, nearly identical to those at the Lang’ata decanting site. Same materials. Five stories. One major difference: Instead of the exclusive 3-room units, the Soweto East relocation site offers different typologies: 1, 2 and 3-room apartments. The idea is that smaller units are more affordable. It remains to be seen. Construction began in 2011 and is expected to be completed in 2014.