How to Pay for Slum Upgrading: The Power of Leveraging Private Funds

For the next step in the Nairobi studio Spring 2013, we are looking into different models of participation and governance (getting the ball rolling and including the community), monitoring and evaluation (assuring outcomes and accountability) and financing (paying for it) of slum upgrading. Assigned to the financing team, I have been learning more about donor- and government grants and loans with or without intermediaries, temporary and long-term tax breaks and debt relief, community savings groups and participatory finance—I could go on.

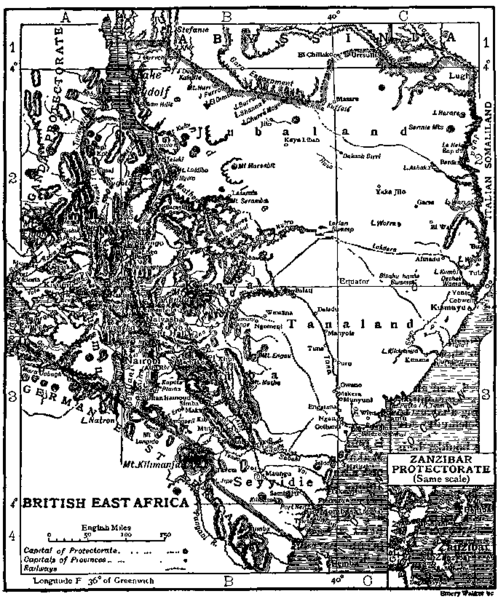

As I was reading about slum upgrading finances in Tanzania, India, Thailand, Brazil and Kenya, I kept wondering about the elephant in the room: the United States. While the United States might not harbor so-called “slums,” as they are often understood or imagined in the conventional sense (make-shift tin-roof shacks, open sewer and steep narrow roads), the United States certainly has (and continuously does) have its own massive share of sub-standard housing and programs to solve the problem.

Several examples come to mind:

–> Hoovervilles in Central Park, New York City, early 1930s during the Great Depression:

–> Pruitt-Igoe as part of a Public Housing Initiative during Urban Renewal in the 1960s:

–> And finally modern-day colonias, mostly found close to the Mexico-USA border:

So how did these work out and what could be learned for Kenya’s national slum upgrading policy, especially in terms of financing?

From these examples, not much. Hoovervilles and colonias are basically informal settlements: both were bottom-up self-financed and -built temporary solutions that became permanent. They do work–as slums often do–but they do not work well. Public housing under Urban Renewal, the only example here built at a large scale and by the government, is not a good inspiration either. It failed miserably:

![Demolition of Pruitt-Igoe in April 1972, St. Louis, Missouri [Photo by U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Office of Policy Development and Research]. Source: http://places.designobserver.com/media/images/ForeclosedRoundtable-2_525.jpg](https://christinagossmanntravels.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/failed-pruitt-igoe.jpg?w=500&h=394)

Demolition of Pruitt-Igoe in April 1972, St. Louis, Missouri [Photo by U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Office of Policy Development and Research].

Source: http://places.designobserver.com/media/images/ForeclosedRoundtable-2_525.jpg

Disappointed, I poke around some more, and finally stumbled upon one interesting financing example: the Cleveland Action to Support Housing or CASH, a funding organization in operation since 1977 as a result of a collaboration between the Cleveland City Planning Commission and neighborhood organizations.

With the goal to increase funding availability from private banks for people of color (during a time of “redlining,” the practice among lending institutions to deem certain neighborhoods as less desirable for loans, based on racial representation), the idea was to maximize private investment by leveraging public monies with private dollars. This way, the lenders’ exposure to risk would be reduced (whether such a risk actually existed or not, as was most often the case). The Cleveland Planning Commisson proposed to use public money provided by the Community Development Block Grant to underwrite any part of the loans and to implement a rotation system for all participating institutions. This means that the little risk there might have been for lenders would be spread over a big pool of participating lending partners. The risk would effectively be eliminated. In addition, lenders would be allowed to occupy four of the five seats in the nonprofit corporation that established a loan-review committee to evaluate all loan applications. The only thing former director of the Cleveland Planning Commission Norman Krumholz and his team were asking was for the lenders to modify their underwriting criteria slightly, so that more borrowers would be “bankable” which in turn would allow borrowers to take out rehabilitation loans to fix up their housing at slightly below the market value.

But lenders refused to modify their criteria to lend below market interest rates.

It was a good plan: effective, safe. But it was the wrong place and the wrong time. The “risk of default,” lenders said, was too strong. What they really meant was that they would not get over their racism. Cleveland’s poor were all black.

In the face of such difficulties, how was CASH finally endorsed? Interestingly, it succeeded partially by proving another program wrong. The primary programmatic vehicle for housing rehabilitation at this time was a government-funded Three Percent Loan Program. Under this program, any qualified applicant could receive a rehabilitation loan of up to $20,000 at an (incredibly low) interest rate of 2% with a term of up to 20 years. This loan, however, had little impact on the rehab needs of the city: It turned out that most low-interest loans were going out to middle-income who used the money to remodel kitchens and bathrooms.

Although the three percept program remained, as it was politically feasible and attractive, CASH advocated had a lobbying ground and after two long years of negotiations, in 1977, it was finally implemented.

Today, CASH loans are made by one of 20 participating lenders at a 2.3% interest rate. The private public leveraging ratio is two for one. CASH no longer targets redlining—yes, it still exists—but it does offer three types of loans, mostly to low-income populations.

So goes my stint into United States house upgrading finance. And while I realize that CASH is not an ideal program and it does not live up to our search for a slum upgrading financing model, I believe that it does offer several crucial lessons:

Lesson 1: Financing requires a (at least) three-way partnership among the government (be it city-, state- or the federal level), community-based development organizations and the private banking sector.

Lesson 2: When we speak about housing provision, credit and rehabilitation can only flow when private funds are leveraged.